by Jackie Nunnery –

Some call it Grit Lit or Southern Noir, others call it just a plain good read. But whatever you call it, Gloucester writer Sean Cosby is currently at the top of this crime fiction genre.

As the saying goes, crime doesn’t pay, but writing about it has proven beneficial for Cosby. His writing explores the violence and underlying desperation of crime while showing the humanity of its perpetrators and victims. His characters inhabit rural South settings that are haunted by history and pain, while showing people striving for redemption or revenge and sometimes both.

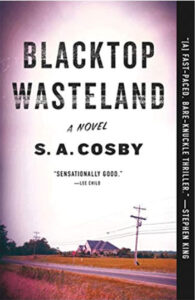

Cosby’s last two novels, Blacktop Wasteland and Razorblade Tears, won numerous awards and mentions, with Razorblade Tears debuting on the New York Times Best Seller list. As if that was not enough, both have been optioned for the big screen.

When we talked, the Mathews native had just returned from a trip to Los Angeles, was finishing up an audio drama to be featured on Audible, and was continuing to work on his next novel.

What is it about the rural South that is so compelling to write about?

Virginia is my heart and my home. I’m a Southern writer and a Southern boy. At the same time, I’m aware of the painful history. Even though I love where I come from and the community I grew up in, you still have to acknowledge the inequalities and the painful circumstances that exist around where we come from. It’s an interesting dichotomy.

When I write, I try to use my writing to talk about those issues. At the same time, nobody loves you like the people you grew up with. Being a writer allows me to articulate the things I love about where I’m from. I’ve got to make sure I’m giving a balanced representation of my hometown and the folks that live there. It’s important to me.

Honesty is a way of showing I love where I’m from.

Following on the old adage of writing what you know, do you have people think they recognize themselves in your novels?

Everybody I went to high school with thinks they’re in a book (he laughs). People at my church think they’re in a book. Honestly, there’s no direct representation of anyone in these books, but there are inspirations. There are characters that are amalgamations of folks I went to school with, folks I didn’t get along with when I was young. It’s interesting to have those conversations. One, it tells you people have read the books and two, it tells you that people have connected with them.

Why did you choose to write crime fiction to explore these themes?

I first started writing horror fiction. I wanted to be the next Stephen King or Clive Barker but for some reason it never clicked with anybody. I’ve always been a fan of crime fiction, but had blinders on that nobody would want to read crime fiction about the South. Later, I came across Daniel Woodrell, sort of the grandfather of what some people call Grit Lit.

Reading his work, I realized there was a way to translate the characters and interesting situations I grew up with into a crime fiction narrative.

I had a friend—I swear this is a true story—I had a friend who was a belly dancer in New York City and after a performance, she and her troupe went to a bar. The bar they happened to go into—and of all things, coincidences are just the universe telling you which way to go—this bar was managed by a guy who also happened to be a crime writer himself. He was publishing a quarterly crime fiction magazine called “Thug Lit” and they were looking for new writers. I was still thinking ‘nobody would be interested in stories about here’ and I told her, ‘when you’re living in a small town, there’s very rarely a whodunit. Everybody knows whodunit, it’s just can you prove it.’

Crime fiction, for me, is the best prism to analyze the things that interest me—people who make hard choices, identity and who we are versus who we want to be.

I’m interested in the people I grew up with and how to translate the microcosm of their lives to the macrocosm. Crime fiction has always been the bridge. It doesn’t matter if you’re from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, poor is poor and desperate is desperate. Crime is the gospel of the dispossessed.

Why do you think readers are drawn to crime fiction?

I think it’s cathartic. The bad guy gets what’s coming to him. It so infrequently happens in real life, that reading it in a novel is incredibly gratifying. Even if what’s coming to them is somebody getting chopped up in a wood chipper (he laughs).

So tell me a little about your writing process.

When I start a project, I don’t do a really extensive outline of everything because I’m lazy, but I do write a pretty extensive synopsis. It’s usually three to five pages and it’s basically me telling myself the story. It’s a guide with story beats. Once I finish the first draft, I have four really good friends who are also writers that I trust to look at it and be honest. You have to develop a thick skin if you’re going to be a writer. That whole process takes nine months to a year. It’s a process I treat seriously, but it’s not a job, it’s a vocation. Birds gotta fly, bees gotta sting, and I gotta write.

Now that you’ve sold your books to be adapted for film, how do you feel about your work being interpreted by someone else?

Lee Child once told me, ‘it doesn’t matter what the movie or the TV show does. The book is always going to be the book.’ Once you make the decision to option something, once you bargain and take their money, you have to accept that. It’s like somebody coming to your house and cooking in your kitchen. You hope they know what they’re doing, you hope they make a good meal, and nine times out of 10 they do. The only thing I was really adamant about was that it had to be set in the South. I don’t care if it’s Virginia or North Carolina, but there’s a certain tone, a certain atmosphere in the coastal area that I think is inherent in the books. It’s not going to work in Topeka, Kansas, the way it does in Virginia or North Carolina.

What other projects do you have coming up?

I’m knee deep in a novel right now. Blacktop Wasteland and Razorblade Tears were books that seemed very operatic in scope and anchored in the pulp fiction tradition because that’s what I grew up reading. There’s nothing wrong with that but I wanted to shift my tone with my current project to a little less pulp and a little more literary. Not too much though, you dance with who brought you to the party.

I don’t take any of this for granted. My mama used to say, ‘the shine wears off of new pennies quick.’ For me, that means you have to enjoy it while it lasts. I know next year there will be the next crime writer du jour. All I ask is that I’m still able to write the books that I want to write, be a writer full-time and tell the stories I want to tell.