Illuminating legacies and igniting brighter futures: Delving into the Hidden History of the Northern Neck

W

hen the Northern Neck Hidden History Trail officially launched earlier this year, U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine said the “innovative, digital experience would provide a new perspective to the centuries of history within the Northern Neck of Virginia. It will serve to uplift the untold history of Virginia’s tribal communities and people of color and will also invite the community to reflect together on the past, present and future.”

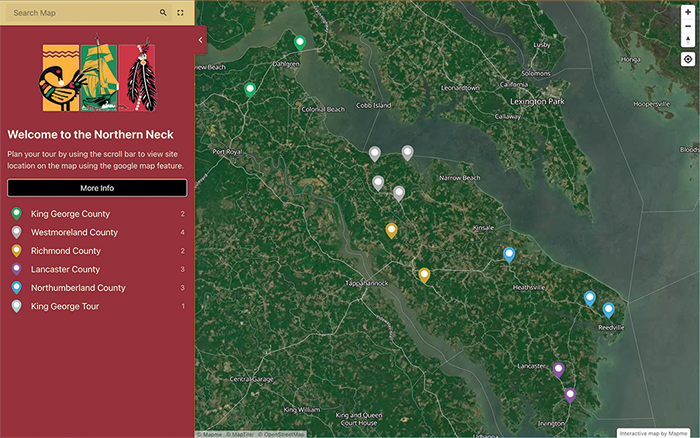

The digital experience that Sen. Kaine spoke of begins at nnkhiddenhistorytrail.org where you will find an interactive map that allows you to plan your itinerary trail by location. The history told through the people in places throughout the counties of Lancaster, Northumberland, Richmond, Westmoreland and King George is intended to present a more inclusive and shared history of African-Americans, Native Americans and European Americans, illustrated through their motto “Illuminating Shared Legacy. Igniting Brighter Futures.”

The digital experience that Sen. Kaine spoke of begins at nnkhiddenhistorytrail.org where you will find an interactive map that allows you to plan your itinerary trail by location. The history told through the people in places throughout the counties of Lancaster, Northumberland, Richmond, Westmoreland and King George is intended to present a more inclusive and shared history of African-Americans, Native Americans and European Americans, illustrated through their motto “Illuminating Shared Legacy. Igniting Brighter Futures.”

History told through the lives of people

Well known historical sites—Stratford Hall, Historic Christ Church or Menokin—are included on the Northern Neck Hidden History Trail as well as pivotal sites we pass by every day on our travels, not realizing their significance.

Dr. Charlton’s House is one of the locations with surprising significance. Located off of Northumberland Highway near Reedville, the house was the home and office of Dr. Jaehn B. Charlton (1917-2004), the first African American physician in Northumberland County and the second African American physician in the Northern Neck, following Dr. Morgan E. Norris Sr. (1883-1966), who practiced in Lancaster County.

Download the interactive Northern Neck Hidden History Trail tour app and you have your own tour guide. In the augmented reality (best viewed by holding your phone horizontally), you can look around and see photos from a meeting of the Rappahannock Medical Society (ca.1949) that shows both men in attendance. Information on Charlton’s patent for a pollution control device and a copy of a historical marker, which includes biographical information, is also included.

Technology is also used to replace what once was, as is the case of Dr. Norris, where an historical marker marks the spot where his office once stood. Select the site in the app and you can listen to Norris’ story while viewing photos of Norris, his office and his homes, which are still standing. Norris’ story includes other locations that Norris was instrumental in building—a service station and a brick schoolhouse—in his fight against the constraints of Jim Crow laws. His story, one of “cooperation and mutual respect” is detailed in Fight On, My Soul, written by his son Dr. James E.C. Norris.

History told through landmarks

A story of determination is told through the schools for African Americans which dot the region. For African Americans, education became an especially important part of Reconstruction, with a number of community schools built through the generosity and dedication of the African American community itself or aided by philanthropic ventures. Although many of these schools are lost to time, there are a few still standing.

On the tour, you can hear the story of Holley Graded School’s two founders, teacher Caroline Putnam and Sallie Holley. The school in Lottsburg is largely unchanged since it was completed in 1933. According to the National Register of Historic Places the first school was “located near the road by a large oak tree” and “was a one-story structure of three classrooms in a row.” The property also included “a teacher’s cottage as early as the 1870s but was demolished around 1935.”

Architectural details inside and out reflect the pride the community took in the building and the education of its children. The most striking feature is the tin panels which cover both walls and ceiling still in their original color scheme of green and white. And while the building was electrified sometime in the 30s or 40s, heat was still supplied with wood stoves, one of which still stands in one of the classrooms.

Originally named Northumberland County Training School, the Julis Rosenwald High School near Reedville was designed by architects at the Tuskegee Institute and constructed beginning in 1916 using funds collected from the African American community. It was finished the following year with money from the Rosenwald Fund. Using the tour app you can hear about Julius Rosenwald and see historical photos of the school.

Although not accessible by the public yet, the school features six classrooms on two floors and includes an auditorium and library. When in use around 1927, the campus had no electricity or running water but included a small elementary school (still there but unsalvageable), and three other buildings devoted to science, home economics, and agriculture. Those buildings no longer exist, but you can see pictures in the augmented reality of the app.

Weaving together an inclusive history

At Menokin, the home of Francis Lightfoot Lee, a member of the influential Lee family of Virginia and signer of the Declaration of Independence, historians are working to tell the interwoven stories of the indigenous people first living on the land along with the colonialists and enslaved African Americans.

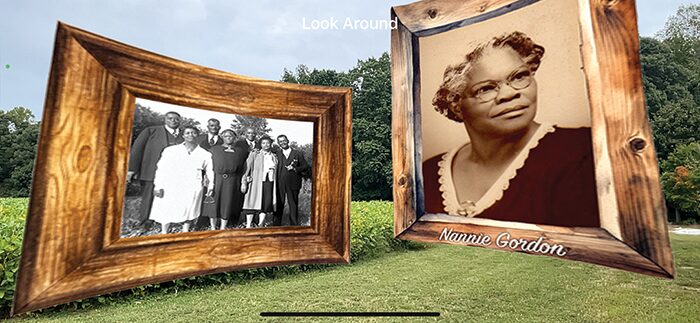

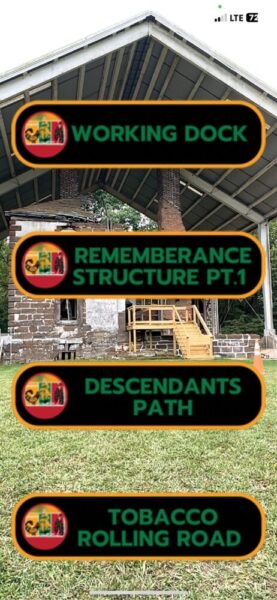

When you arrive at Menokin’s Visitor Center, you can read the story of Daniel West Gordon, born into slavery. Not much about his early life is known, but Gordon returned to Menokin around 1867 as a tenant farmer. Step outside to the Descendant’s Path and Gordon’s legacy is shown through photographs of the Gordon family. Along the path there are trees planted representing family names of those enslaved on the property—Gordon, Henry, Parris, Beverly, Smith and Cox—leading to the Remembrance Structure, a representation of a dwelling for field slaves. While on the property, the tour will also take you to the Tobacco Rolling Road and the Working Dock, to hear about the operations of the tobacco plantation, as well as to the ruins of the stone tenant’s house.

While the collecting of indigenous artifacts from the property continues, director of education Alice French said plans are underway to tell their story. “We’re working with the Rappahannock [tribe] to see how they want their stories told.” French said projectile points and cord pottery estimated to be from 900-1200 A.D. have been found. Currently, the Rappahannock are recognized through the Heritage Garden, a living exhibit illustrating the “three sisters” method of growing crops. Corn is grown on a small hill, with beans grown around, using the corn stalks as a trellis. Squash is interspersed through the growing field.

Menokin’s outreach and interpretation associate Kayla Payne said the interesting thing about the history of the plantation is that it is told in “bits and pieces.” The most striking is the ruins of the house, currently under restoration with the Glass House Project, but now the remnants of the enslaved and indigenous people are being examined. “You have the pieces of the house, the history of the enslaved and indigenous people and you’re weaving together” a more complete picture of the property.

Menokin’s outreach and interpretation associate Kayla Payne said the interesting thing about the history of the plantation is that it is told in “bits and pieces.” The most striking is the ruins of the house, currently under restoration with the Glass House Project, but now the remnants of the enslaved and indigenous people are being examined. “You have the pieces of the house, the history of the enslaved and indigenous people and you’re weaving together” a more complete picture of the property.

The same is true for Historic Christ Church in Weems. The story of the church and surrounding property is one of intertwined family legacies. The rich and powerful Carter family headed by Robert “King” Carter and the enslaved families of the Corotoman plantation. It is also the remarkable story of his grandson Robert III, who inherited vast wealth in land and slaves and chose to give much of it up by freeing the slaves. You can hear the story of the 1791 Deed of Gift and see a copy of the document as you tour the church property.

Points of interest

Other points of interest do not have buildings attached to them. Currioman Boat Launch in Westmoreland County and Totuskey Boat Launch in Richmond County represent a shared history between colonists and indigenous around trade.

The Hallowes site on the Currioman Bay of the Potomac River, acted as a major place of interaction for the Indigenous people of the Northern Neck and the new European immigrants from the 1640s to the 1660s. Archeological excavations conducted in the 1960s included traded items of pottery, bone pipes and deer remains, all of which can be seen in augmented reality. At Totuskey Creek, the natural beauty of the site and the story of the tribe tied to the Rappahannock is highlighted. “Totosha” was a seasonal village where they fished for spawning shad and herring in the spring for food and trade. On the app you can read a copy of the highway marker—safely away from traffic—and see Rappahannock artifacts.

Just as history is discovered and told in bits and pieces, the Northern Neck Hidden History Trail is an innovative telling of history in a digital format is never set in stone. Co-founder and program director of the trail, Alva Jackson, said the website and app will continue to be updated with new locations and digital artifacts to give a richer sense of the people and their stories that have enriched the region for generations.