This article was originally published in the Fall 2015 issue of The Rivah Visitor’s Guide.

by Larry Chowning –

In the summer of 1961, just off Stingray Point in the Chesapeake Bay, 12-year-old Robert Allen “Beady” May hooked a 75-pound stingray, a catch of a lifetime, and a fishing moment that sparked a lifelong friendship.

After a 45-minute fish fight, the giant stingray came over the side of the boat. Charter boat Captain J. Dewey Norton dangled the ray’s poisonous tail down into a bucket full of Clorox. The brown skin on the tail quickly turned white as the bleach killed the poison on the spear. Dewey cut the white tail off and passed it to Beady as a reward for his catch. The captain moved back to the helm, picked up a lit corncob pipe filled with Prince Edward tobacco, took one puff, grabbed the wheel, and with a tinge of excitement said, “’You did all right boy! Dog-gone that’s a big stingray!”

That would be a lifetime memory unto itself, but the story gets even better.

Beady was born in 1949 in Richmond. He got his nickname Beady as a baby because of his small, round, gleaming “beady” eyes. When his father first laid eyes on him in his mother’s arms, he remarked, “He certainly has beady eyes”—a nickname that stuck.

After World War II, an influx of Richmond folks began buying waterfront lots on the Rappahannock and Piankatank rivers and building summer cottages. Beady’s maternal grandparents bought a lot on the Chesapeake Bay in Deltaville. Land developer Eddie Harrow sold them the lot on Stingray Point for $2,000 and built them a cottage for another $5,000. Beady’s paternal grandparents bought a waterfront lot in Dunnsville on the Rappahannock River and built a small cottage there.

When Beady came along, he would spend his summers with his parents at their Rivah cottage. Sometimes the family went to their Rappahannock River cottage, but more often they went to their cottage at Stingray Point.

For several summers a gentleman from Winchester rented a cottage close to Beady’s grandparents’ cottage in Deltaville. Every year this man chartered a fishing party boat and invited the young people in the neighborhood to go along. He either hired Captain Titus Jackson or Captain Dewey of Deltaville, whoever was available. It was on one of those trips that Beady caught the big ray.

“After that big catch, Captain Dewey knew me as the boy who caught the big stingray, “ said Beady, now owner of Hudgins Pharmacy in Mathews Court House. “The next summer (1962) I’d go over and see him and he’d invite me to go along on his fishing party as mate. He did not pay me anything then, but just going was pay enough.”

The next summer in 1963 Beady went fishing with Dewey every chance he could get, and near the end of summer in August, as a token of his appreciation, Beady purchased a new rod-and-reel from Hurd’s Hardware in Deltaville and gave it to Dewey as a gift.

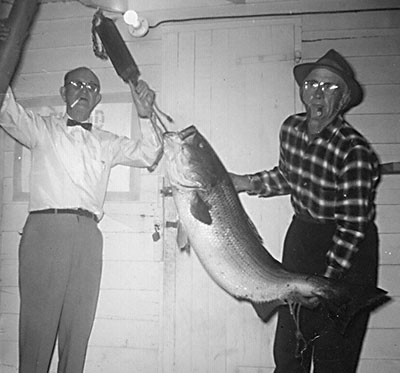

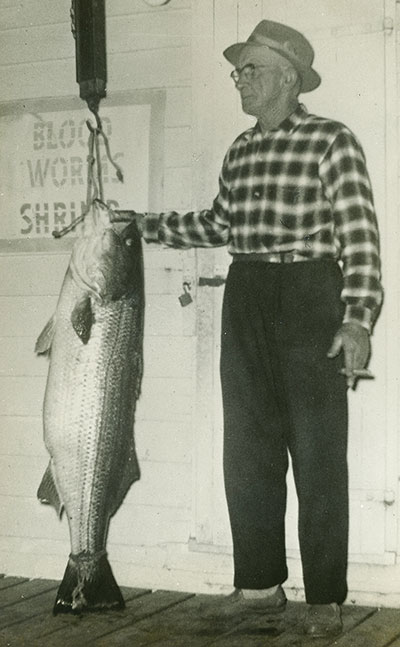

In November of that year, Beady got a phone call from Dewey. “Beady you ain’t going to believe this, but I caught the state record rockfish yesterday with the rod-and-reel you gave me,” said Dewey.

On November 18, 1963 while trolling off Gwynn’s Island in the Chesapeake Bay, Dewey caught the state record 58-pound, 8-ounce, 52-inch-long rockfish on Beady’s gift rod. The previous state record had been 45 pounds. Shortly thereafter, Richmond Times-Dispatch outdoor sportswriter Max Ailor arrived at Captain Dewey’s doorstep at his home on Jackson Creek, and for several years filled his columns with information on the man he called “Dean of Virginia Charter Boat Fishing.”

Fishing Parties

Dewey guided fishing parties for over 50 years and was known as an innovator in the field, particularly in the early years of cobia fishing. He was one of the first guides to really go after cobia. At that time, the knowledge of the fish was so vague that Dewey and others called the cobia “bonito,” a fish that is not even related to cobia.

He and others were trying to catch the fish on hand-lines and dip-nets. It was not working so well. In a 1967 Times-Dispatch article Dewey said “We used hand-lines and I don’t know how many we lost trying to get them into the boat. I didn’t have a gaff and we tore up landing nets and everything else we had onboard.”

Dewey, always innovative, went to the junkyard and found an old radius rod from a Model-T Ford and made a gaff of that. “I used that old rig until saltwater ate it up,” he said in the interview.

He was also one of the first in the area to use chum to catch bluefish. “We had heard they were chumming for blues at Hampton Roads so I went and found some alewives to make some chum. Everyone used to say bluefish didn’t come into our area because we seldom caught any. We proved they were wrong that day, and then most everyone went to chumming,” Dewey told Ailor.

After the summer of 1963, Beady continued to work a little here and there for Dewey until he graduated from high school. When he went to college it looked like the end of their summers on the boat together. Beady graduated from Hampton Sydney College in 1972 and in 1974 got his Masters degree from the University of Richmond. That September, he started teaching at Lee Davis High School in Richmond.

“I realized teaching gave me the summers off so I came down to the (Deltaville) cottage and I renewed my relationship with Dewey. For three summers I went out with him every day when he had a party. We developed a friendship that I will treasure for the rest of my life.”

They fished from the boat “My Lady,” a square stern wooden deadrise boat that Dewey built himself in his front-yard. Dewey had owned two other boats, “Velma” and “Velma II,” named after his daughter. He encouraged Beady to get his captain’s license, and on January 10, 1976 he earned his license and his radio/telephone license.

“One morning I went over and Dewey wasn’t feeling well,” said Beady. “His wife Catherine (his first wife Alice passed away and he had remarried) came to the door and said Dewey was sick and wanted to talk to me, so I went upstairs.”

During this part of the interview Beady paused to control his emotions. “My true graduation came that day,” he continued. “He was in the bed really sick. He said to me, ‘Beady I can’t go today. You’ve got your license. You take them. You are qualified, go take them.’ We were scheduled to go cobia fishing.

“I took them fishing and we got two cobia and I brought them back to Dewey’s dock,” said Beady. “Dewey was still sick the next day so I took the next group too.

“Of all my professors I had in school and life, I think Dewey taught me more than all the rest. I got an education in life that you couldn’t get in a classroom anywhere. He had a charisma about him that came from his culture and a wonderful dry sense of humor.” said Beady.

“Dewey knew what his day was going to be like long before me,” Beady continued. “I’d get down to the boat and he’d say, ‘We’ve got an insurance group coming down and they will probably be drinking (alcohol). We need to watch them close to make sure they don’t do anything foolish.’ “

Captain Dewey was not a fan of alcohol aboard his boat.

“If anyone started to misbehave, I’ve seen him throw the alcohol overboard and take the entire party back to the dock,” said Beady.

“Some of the parties brought food and shared it with us, and Dewey knew which ones would and which ones wouldn’t. He’d say to me the day before, ‘You better bring your lunch tomorrow Beady, they ain’t going to feed you.’ ”

Dewey’s years as a schooner captain sailing the bay provided him with insight and understanding of predicting the weather. “Some mornings the sky would be clear but if Dewey headed up the Piankatank River, I knew before the day was over we’d run into a summer squall,” said Beady.

The narrow Piankatank provided better shelter from gale winds than the Rappahannock River or Chesapeake Bay.

The only electronics on the boat was a Pearce Simpson radio. “Dewey’s call name was Whiskey November (WN) 2815. He didn’t need a Loran or radar because he knew where all the good fishing holes were and he knew how to get home,” said Beady. “There was Corn Hole, Covington Ridge, Deep Rock, Butler Hole and Cherry Point, and Stump Farm was usually good fishing located right off the campground on Gwynn’s Island. Dewey knew all the good places.”

Captain Titus Jackson kept his deadrise charter boat “King Bee” at Dewey’s dock on Jackson Creek in Deltaville. Beady recalled that the two captains had a friendly, humorous relationship.

“One day, Titus and Dewey were out fishing with their parties when a captain from another charter boat came over the radio to announce one of his patrons had caught a 28-pound striper. Titus radioed Capt. Dewey, ‘Would you say anything on the air about a 28-pounder?’

“ ‘No,’ ” answered Dewey. “ ‘I use fish like that for bait.’

“Another time we went over to fish off Silver Beach on Virginia’s Eastern Shore,” recalled Beady, “and we filled a big, big trash can up with croaker. He tickled me because whenever we filled the big trash can full, he’d look over at me, wink his eye and he’d say to me in a whisper, ‘Won’t be long before we’ll be going home,’ meaning the party would soon get tired of catching and start thinking about having to clean all those fish.

“Oh my gosh, he hated to see people come down with fishing rigs that had a sinker at the bottom of the line and two leaders with hooks extending out. He called them antennas. With those rigs, most people did not catch much. When they’d turn their backs, Dewey would cut their line, attach his own rig, and nine times out of ten they’d start catching fish,” said Beady.

“He had dedicated customers. When he caught the state record rockfish, he was with a party from Ohio that had been coming to fish with him for 15 years,” said Beady. “Two members of the party had caught fish weighing 17 and 18 pounds on their first day of fishing. The following day the big fish (state record rockfish) hit.”

In an interview with Ailor shortly after the catch, Dewey said, “It made three long runs. I didn’t know what I had. You never can tell what you’re going to catch in the bay. That’s what makes her interesting. I didn’t see the fish until I brought it into the boat to gaff it.”’

Every morning, when Beady arrived at Dewey’s house, breakfast was ready for him—eggs and a piece of toast. “We’d come in from a day of fishing and go up under a big oak tree in Dewey’s yard and we’d converse sometimes. We’d talk about life in general and I’d go home to the cottage, sit on the front porch, and look at the bay. They were three wonderful summers.”

After three years of teaching, Beady decided he wanted to do something different with his professional life. He got married in 1977 and he and his wife moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he enrolled in pharmacy school. When he got out of school he moved to Tappahannock to be close to Dewey and the bay.

“He was really like a grandfather to me,” said Beady. “He was down to earth. There was no foolishness when we were on the boat. He was of old English stock. It was a relationship that I have never experienced since. I feel for people who have not experienced it.”

Beady has some memorabilia left from those treasured times. He is proud of his framed copies of his captain’s license and his radio/telephone license, both inspired by Dewey. He has a Christmas card, dated December 18, 1975, that he received from Dewey and his wife. In the top righthand corner of the card are some words written by Dewey, “Hot toasts makes the butter fly!”

Dewey Norton died at the age of 82 on August 26, 1980. At the time of his death, he still held the “certified” Virginia Saltwater Fishing Tournament rockfish record. John P. Lewis of Stevensville broke Dewey’s record on April 10, 1981 by landing a 61-pound rockfish in the Mattaponi River. The current Virginia record of 74 pounds was caught in 2012 by Cary Wolfe of Bristow in the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Henry.